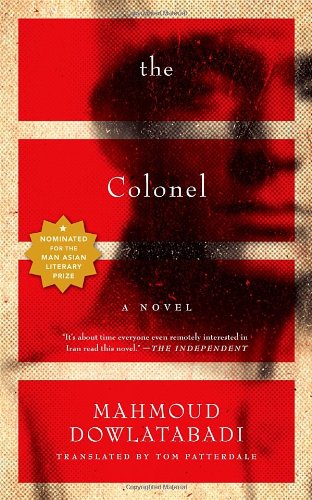

Dowlatabadi's The Colonel reviewed by Donna Honarpisheh

Awarded the 2011 Man Asian Literary Prize

Paperback: 250 pages Publisher: Melville House Publishing (April 2012)

Original Language: Persian Printed in: English

Reviewed by: Donna Honarpisheh

The story of The Colonel unfolds after the Iranian revolution of 1979 towards the end of the Iran-Iraq war (1980-88), a time Dowlatabadi describes as being infused with continuous brutality and chaos. Dowlatabadi shows us that the Iranian revolution and revolution in general, is not a linear development and in its course, lives are claimed on many fronts. Dowlatabadi wastes no time in narrating these horrors, in the opening scene, a father is called in the middle of the night to collect the body of his 14-year-old daughter, who has just been executed by the authorities of the country.

By structuring the novel in a way that contains layers of multiplicity, a common theme in Dowlatabadi’s novels, he creates a narrative, with the central voice belonging to the protagonist, the unnamed colonel himself. The character of the colonel is meant to symbolize a former soldier with principles who was meant to serve the interests of his country, only to find himself in an existential frame of mind as corrupt as his enemies. Dowlatabadi uses a choppy narrative that almost feels like he is interrupting himself. By emphasizing the complexity of situations, Dowlatabadi makes clear the subjectivity of human thought. The centrality of the colonel’s innermost thoughts allows for greater understanding of the depth of this character, allowing readers to identify with a man who has murdered his wife.

“Maybe I’d lost my senses, or was it that I’d finally come to them at last? What are one’s senses, anyway?”(23)

The chaos described is not simply that of bloodshed, but of the mind. As literary scholar Hamid Dabashi suggests, the voice of the colonel is often expressed by horrid “hallucinatory implosions.” These introverted and self-absorbed echoes are memories that the protagonist is condemned to remember. Dowlatabadi shows us that the revolution consumed everything, it became everything. A novel deeply rooted in historical context, we are introduced to each revolutionary group: Mujahidin khalq-e Iran (Armed Terrorist group), Tudeh (Iranian Communist Party), Nationalists, and Islamists; each struggling to progress their own competing outcome for the revolution. Problems and differences arise at every layer of the societal sphere, not only between political groups but between family members, where brother and sister, father and daughter, husband and wife, all oppose each other with differing perspectives. The colonel’s family represents a nation both united and divided by differing revolutionary ideologies. The following lines are central to the theme of the narrative and allow us to enter the colonel’s deepest thoughts about the revolution. In the novel, the colonel uses his three sons and two daughters allegorically, as representative of the various ideological strands in the revolutionary upheavals within one nation. Similar to the idealistic ideologies they supported, none of the colonel’s children survive the toll of the revolution.

“I walked a very straight line, my dear children. But none of you cared about the others and you all went charging off in different directions. What’s the matter with you all? You’re all one family, but you bark up different trees! What is it that you are all after, that keeps you so much at each other’s throats? Are you all living on different planets?

No, in fact they were living on the same planet. But each of them reckoned to have found their own answers to life. They showed me respect but, at bottom, they did not believe in me. When it came down to it, they saw me as an officer of the Shah, although they granted that I’d had no part in the crime that was Dhofar. But even that couldn’t prevent them from regarding me as a creature of the old regime.” (28)

Mahmoud Dowlatabadi’s The Colonel is a novel about Iran’s 1979 Revolution and the paths taken by various people in the midst of chaos. The novel was originally written in Persian in the early 1980’s but has recently received Western press due to the 2011 translation by Tom Patterdale. The English version of the book is advertised as being “BANNED IN IRAN.” Considering Dowlatabadi’s immense popularity in Iran, I became skeptical of this statement and did some research. The book is in fact not banned but has undergone a delayed publishing process. The reason for this is unclear. In a New York Time’s interview, Dowlatabadi explains: “I have written things that if you read them they create questions in your head,” but he added: “I did not do it confrontationally, against the state. In fact it’s a good thing for the regime — past, present and future — to have the experience of writers who work within the system. This has to be an established norm or practice in our country: that people who have different opinions can rationally disagree. It shouldn’t be that I want to kill you, I want to confront you or I want to leave.” Dowlatabadi has been offered to have work printed in Persian outside of Iran but he has refused this offer and has said that as an Iranian, his book in Persian was written for Iranians in Iran. To say the book is “banned” is a false statement but to say that it has ruptured our static image of the 1979 Iranian Revolution in unthinkable ways, is completely true.

I read The Colonel as I would any philosophical tale, taking from it a dark meaning that lingers in my mind, over and over again. The fear, betrayal, struggle, and torture described in this novel is not unique to Iran (as much as Western audiences may like to describe it as such). In reading this novel, I advise a mind that is open to the reality of a revolution. The moral of Dowlatabadi’s story is direct: no revolution is clean. The Islamic Revolution is known to be one of the most popular revolutions in history, with its magnitude in followers. However, even with a resulting success for Iranian society and the ultimate downfall of the Shah, no revolution occurs without bloodshed and resistance to change. Lives are sacrificed, the “families” of a nation are divided, and society, must ultimately be rebuilt by its members, hand in hand. The Colonel is a painful read, yet one that is impossible to put down. Dowlatabadi breezes through literary, social, and moral taboos, sparing no one, a similar tactic of any warring revolution.