Frida at the Brooklyn Museum: Appearances Can Indeed be Deceiving

Though I love and greatly admire Frida’s work, I’ve never actually seen it in person. When I heard of this exhibit, I was really excited - I love the idea of a more personal engagement with this monument of an artist, especially because it allows a glimpse into work you can’t easily find on the internet.

This latest exploration of Frida’s legacy is currently on view at the Brooklyn Museum. Titled Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, the show is comprised of more than 300 of Frida’s personal items that were found in a somehow unexplored bathroom (??) in La Casa Azul, the artist’s former home which now operates as one of Mexico’s most popular museums. These items were discovered in 2004 and have been shown in Mexico and London. This, however, is the first time that the items are being shown in the United States. I unfortunately have no pictures of the exhibition as photography was forbidden.

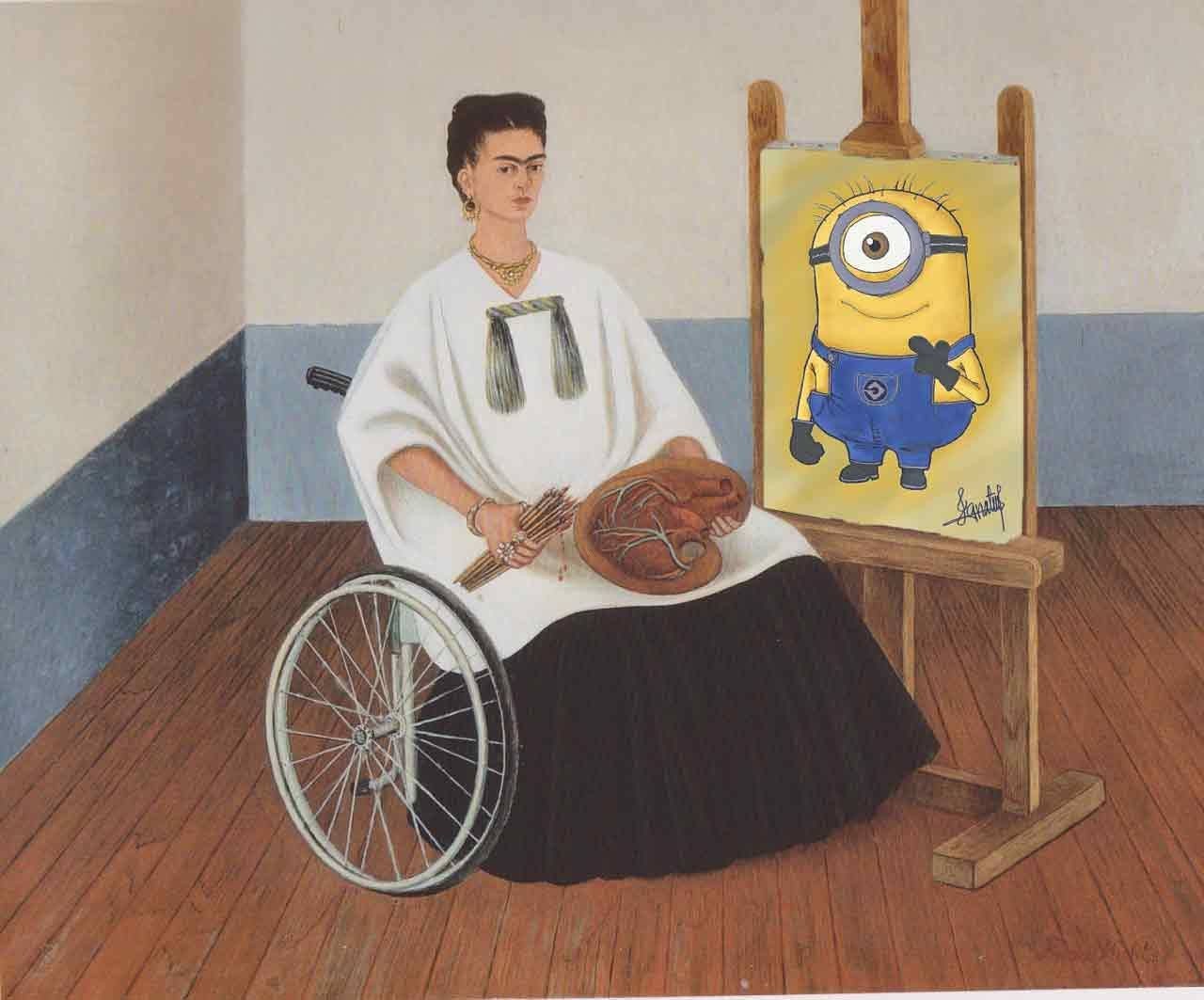

Frida is one of those artists who has been elevated to the realm of myth and near sainthood-- or as we say in late capitalism, Frida has become a brand. You can find her on tote bags and keychains, she’s been immortalized as a much-protested Barbie doll (not enough unibrow), there’s a whole Hollywood biopic about her, and she even cameos in a Disney movie, “Coco.”.

Though her legacy has been explored and exploited in various ways and to various degrees, outside of the pervasiveness of Frida the brand, she remains a compelling artist because of her depth - a queer disabled communist feminist Mexican painter whose work grappled with the complexities of identity.

The thesis of this exhibition is that Frida’s multicultural assemblage of clothing was a revolutionary approach to identity construction. Though the exhibition attempts to contextualize exactly what about Frida’s approach was so revolutionary, it drops a lot of points in this argument without substantively connecting them and leans on Frida’s reputation rather than the strength of curation. In doing so, it inadvertently contributes to indigenous erasure, and completely glosses over the complexities of racial identity in Latin America. I actually found this exhibit quite offensive, especially because Frida is the introduction for many gringos to Latin American racial identity.

I’ll limit my analysis of the problems with this show to two major points. To begin, the exhibit didn’t substantively question and frame how Frida’s identity construction was informed by her elite status.

Guillermo Kahlo, Frida’s German expat father. He changed his name from Wilhelm. Similarly, Frida changed the spelling of her name to make it less German.

There’s mention of Frida’s German expat father, but no substantive analysis of how Frida’s attempts to formulate herself as Mexican are deeply influenced by the caste systems imposed by the Spanish in the wake of native colonization and genocide. In a nutshell, being mixed, or Mestiza, as Frida was, comes with a fair amount of material and cultural advantages. To be clear, there are class stratifications even in mestizx identity, and Frida was part of the elite. One of these material advantages, which the exhibit completely glosses over, is that Frida had indigenous maids. She acquired a fair amount of the clothing this exhibit celebrates from her maids, yet the exhibit primarily highlights the indigenous clothing and textiles that (elite) friends gifted her from their travels.

Frida’s maids would have been subject to stigma for wearing the same clothes that Frida wore to make a statement of national pride, a statement so authentic and bold it has made her a beloved figure of Mexican identity.

Rosa, a working-class mestiza woman in Puerto Vallarta who made a quesadilla so delicious I ate it three days in a row. Check out her apron - Frida is a beloved figure.

Though the exhibit has films of indigenous women, there is NO analysis or reference to the caste dynamics in Mexico, and this, in turn, makes the function of those films tokenizing. They show and celebrate indigenous women as symbols with no substantive engagement with the social context they existed in. To make this legible to an American racial context, this is almost (but not quite) like celebrating a slave-owning woman for her revolutionary uses of cotton that slaves picked, and then playing cute videos of the slave women to provide context.

My other huge problem with the show was about access to the work. In order to access the exhibit, you must reserve a ticket for a particular time, and you are only allowed to view the show for a limited amount of time. The exhibit then opens into a gift shop. I can’t help but think of how deeply ironic this is and how Frida, the communist, would take this display of her legacy.

My overall take? The curators at the Brooklyn Museum are attempting to make Frida legible to the white gaze, as opposed to challenging the white gaze to reconsider and grapple with the complexities of racial identity in Latin America, which is an incredible opportunity to deepen the racial dialogue in this country.

There are few Americans who make the connection that the brown skin of many (but not all) Latinx people indicates some kind of colonized indigenous ancestry. This is an overall problem with engagements with race in the United States - there is still deep fear with talking about Black/white racial dynamics, so much so that the indigenous genocide that enabled the growth of this country is rarely spoken about. As a result, there is no overarching analysis of how indigenous erasure in the States is connected to indigenous erasure in Latin America.

We are currently in the midst of a border crisis, where racially mixed people of indigenous and African ancestry (there were Black slaves in Latin America too!) are being displaced due to the US’s exploitation of Latin America’s resources. Migrants are literally being rounded into concentration camps in a continuation of the genocide this country is founded on.

Claudia Patricia Gonzales, an indigenous Central American who was shot point blank in the head as she entered the United States in 2018. She was unarmed.

Beyond this enormous conceptual oversight, which I find utterly depressing, I find this exhibit especially disappointing because the Brooklyn Museum has been making concerted strides in its engagement with the local community, which is seen most tangibly through its First Fridays, when the museum is open in the evening for an all ages party.

I interacted with this exhibit twice. The first time, I got a ticket and walked through during my allotted time slot. The second, I went to the Brooklyn museum’s First Friday with a couple of friends. I love First Friday because it’s an opportunity to interact with art in a non pretentious way, and because it attracts a much more relaxed and all ages crowd. We were slightly tipsy and running up and down the stairs, giggling and taking selfies and moving from room to room, concocting elaborate conspiracy theories about the why the Egypt ward was next to the Jaden Smith exhibit. We tried to go into the Frida exhibit, but all the doors were locked (you can at least watch Eisenstein’s Que Viva Mexico, which complements the show).

When writing this review, I spoke to a few people who saw this show at La Casa Azul and had nothing but praise. Not having seen the show in Mexico, I can’t help but think that Frida being curated by people who have more understanding of the cultural context from which she emerged would create a better show.

As this exhibit stands, I can’t really see it doing much other than validating the wanderlust and appropriative impulses of culturally confused and conflicted spectators. And for all her faults, I still think that Frida is an important figure with a lot to offer. Frida is so well-known and regarded that the curators could have used this show to challenge casual art viewers. This is a tremendously wasted opportunity. The title of the exhibit is honest, at least.